My Noose Around that Pretty's Neck

TL;DR

In this essay and series of works I attempt to reconcile the work and life of artist Matt Baker (1921-1959) with the sometimes deadly contemporary perception of black men as criminals and sexual aggressors. Baker is often considered to be the first African American comic book artist. But more than his position among the ranks of the heroic Firsts in the black community, Baker is known best for his unique talent as a “good girl” artist. His pin-up styled comic book heroines captivated the imaginations and aroused the libidos of the predominantly white male readership targeted by early comic book publishers.

To be certain, there is an uncomfortable and undeniable irony in Baker’s position. During Baker’s life there were almost 400 reported cases of black people put to death by white mobs, a figure which only includes cases that resulted in the victim's death and were publicly recorded by the press. This number pales in comparison to the estimated 3,446 black people lynched between 1882 and 1968 for crimes ranging from homicide to “insulting women.” Alleged rape of white women became a particularly powerful justification for mob violence, building on existing stereotypes about the biological inferiority and voracious sexual appetites of black men.

How should we understand the heroism of a black man whose work is predicated on providing provocative images of white women during a historical period when he could have been beaten, maimed or lynched for simply speaking to them? Contextualizing Matt Baker’s work in the formulaic wish-fulfillment function of comic books provides a useful lens for decoding the narratives which led to thousands of lynchings across the country and continue to hyper-sexualize and dehumanize black men. Within this context Baker’s female heroines may serve as apt surrogates for the similarly objectified black male bodies.

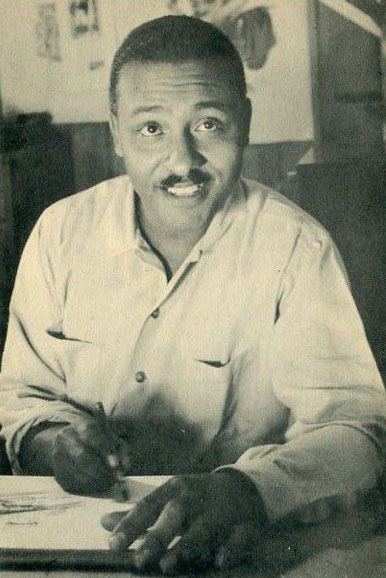

Matt Baker

Clarence Matthew Baker was born in 1921 in Forsyth County, North Carolina. In the 40s, Baker’s family joined the vast migration of black people moving northward in pursuit of economic opportunity and social mobility. Baker moved first to Pittsburgh Pennsylvania with his family and eventually re-settled in New York City to pursue his creative interests.

Aside from limited biographical details and commentary on his social and professional life from friends and family, not much is known of Matt Baker. After completing artistic studies at Cooper Union in New York, he entered the comic book industry as a penciler and inker at the Jerry Iger Studio. The studio functioned as an early comic book factory or “packager” that systematized the way the art and stories were produced and passed them on to publishers and distributors. At the time the work of comic book artists was largely anonymous, and Baker’s was not a prestigious role. Writers, rather than artists were given title credit for published comic books, and at comic shops like the Iger Studio pencilers and inkers could be most closely compared to members of a production line. According to Will Eisner, co-owner of the Iger Studio, in the world of commercial art, professions in the nascent comic book industry ranked “just above pornography.”

In the last decade Baker’s art has been revived, and with it the praise of the man as a historical “first” for the African American community. Baker’s brand of heroism can be categorized alongside hundreds of individuals who are praised for their sometimes intentional sometimes unwitting success at making inroads into social systems that seem stacked against them. The Firsts are praised for their successful navigation of societal prejudice and institutional barriers to expand the realm of possibility for their communities. They are the Joe Louis’, Jackie Robinsons, Sidney Poitiers and Barack Obamas. Like most modern superheroes the Firsts often serve for us a therapeutic purpose. They allow us to resolve tension between two opposing worlds by bridging the gap and embodying the best virtues of both sides. Through them we can add a definitive chronology to historical progress, however we define it.

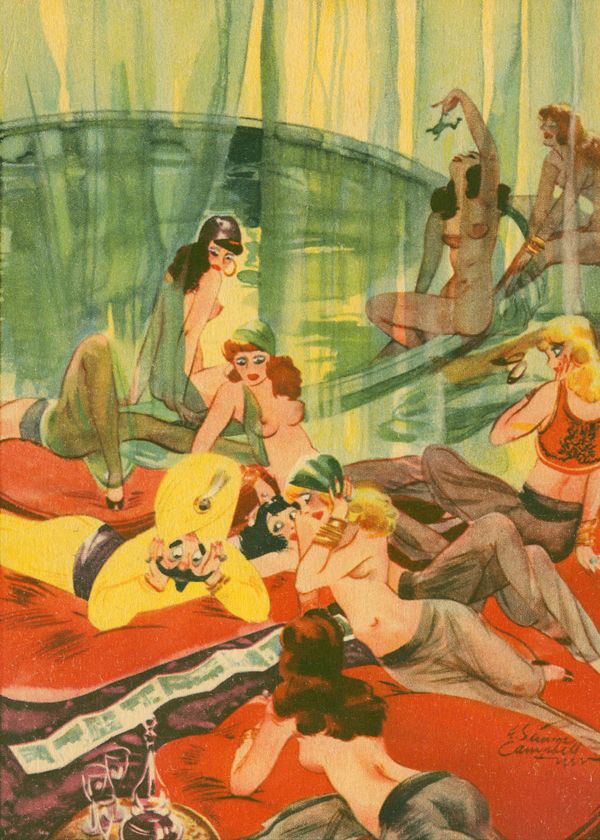

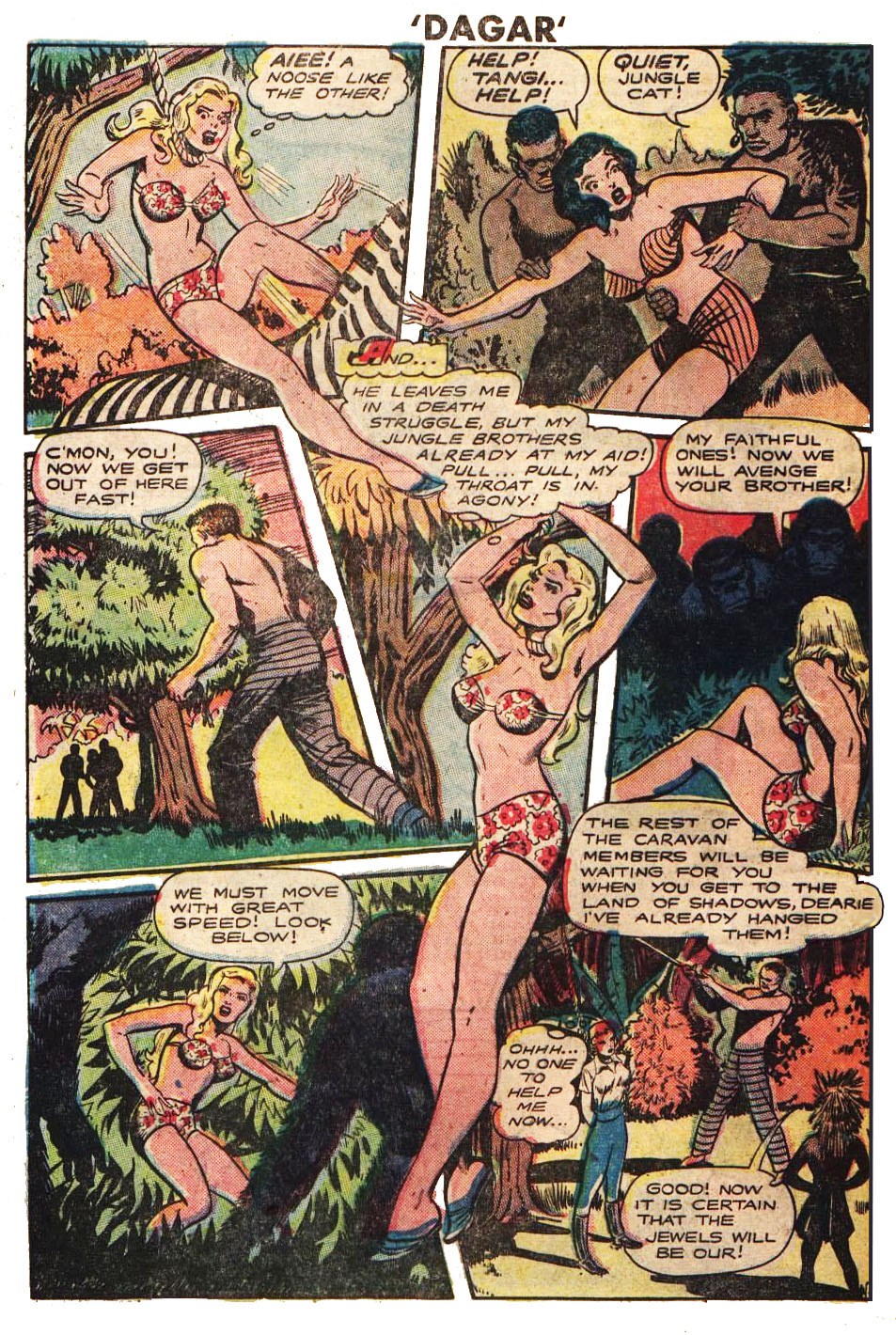

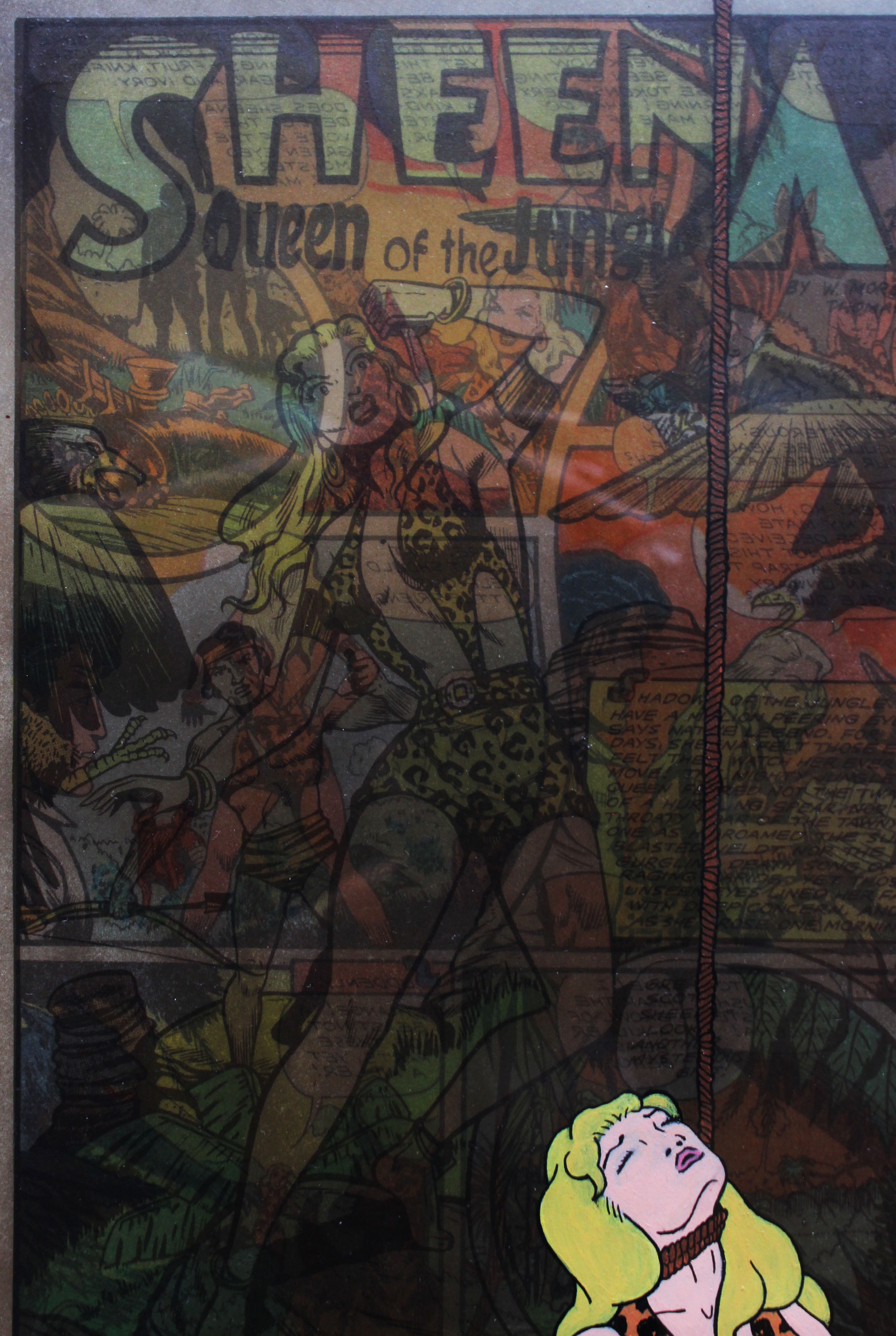

Good Girl Comics

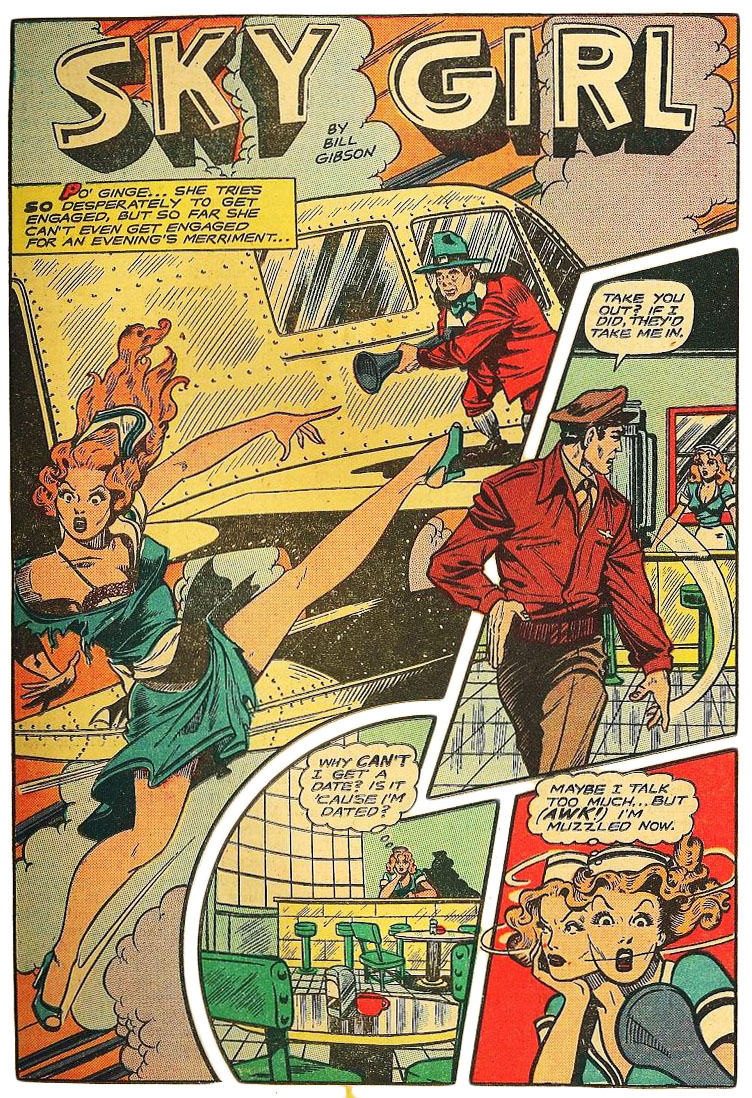

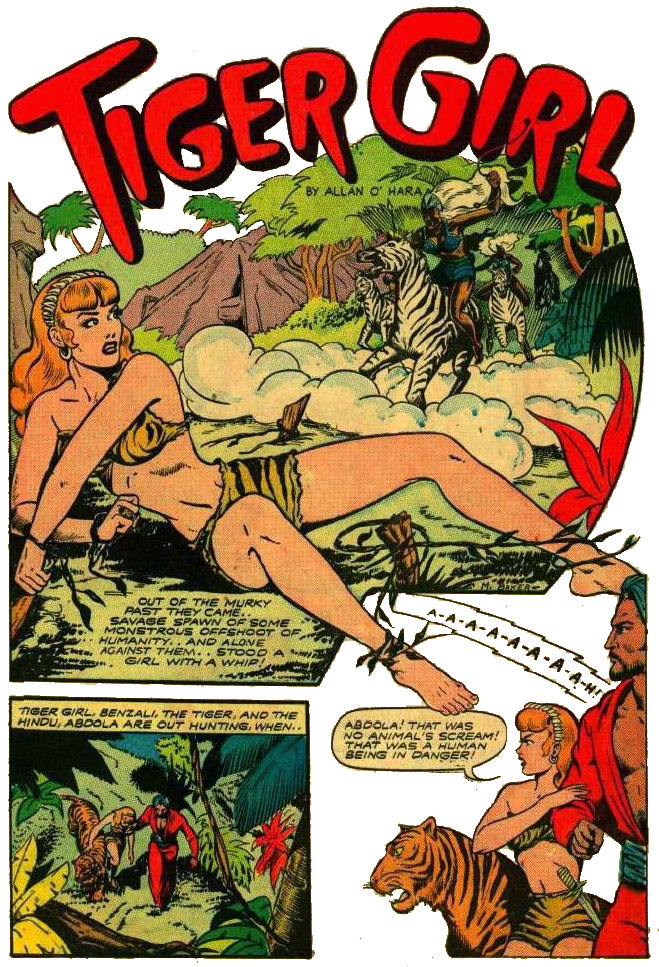

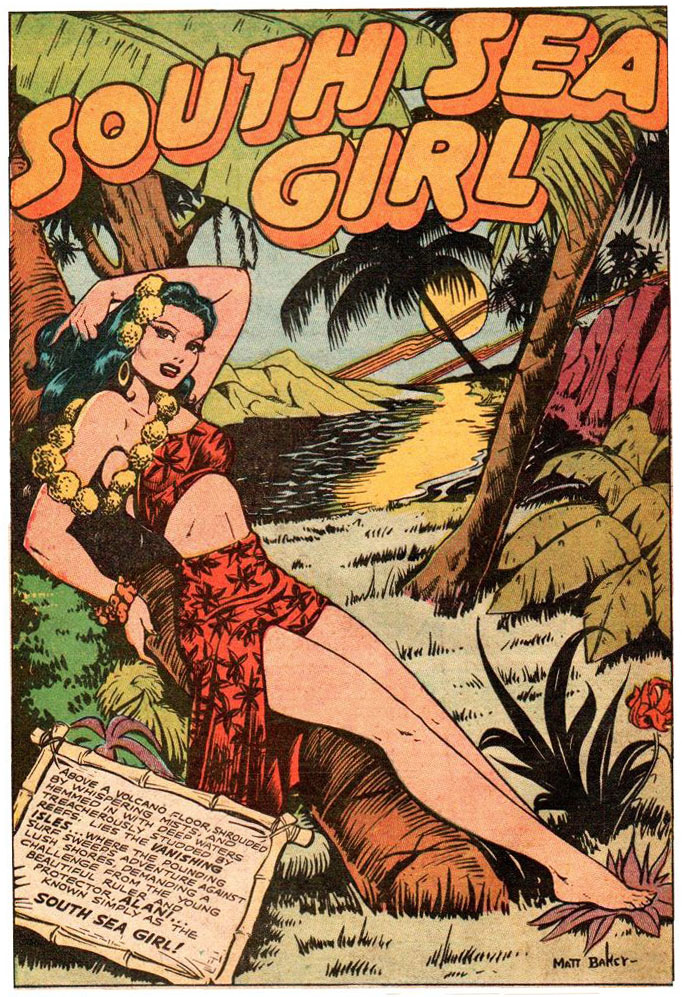

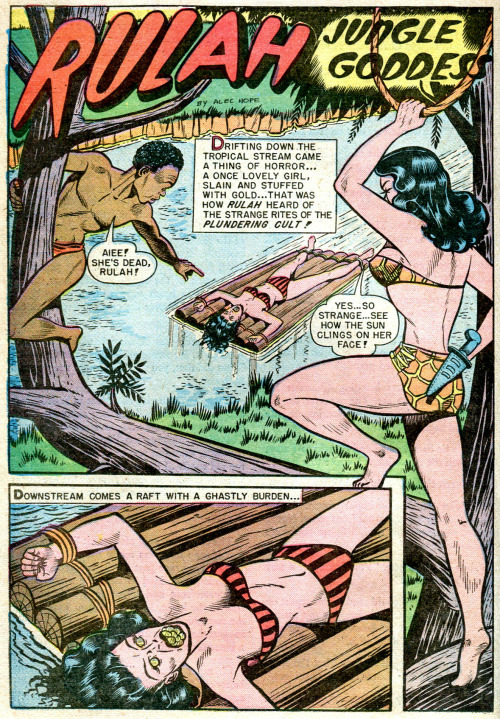

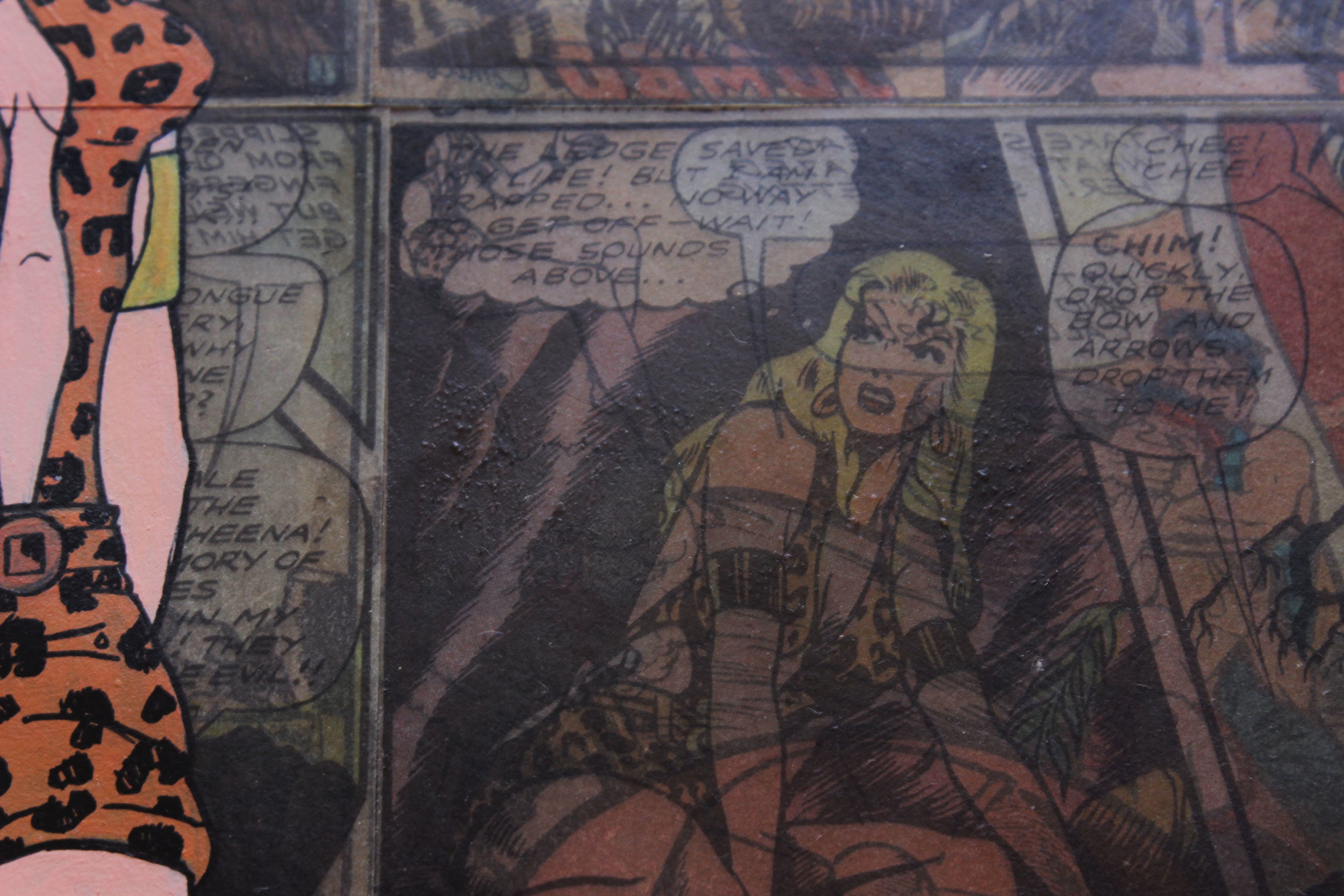

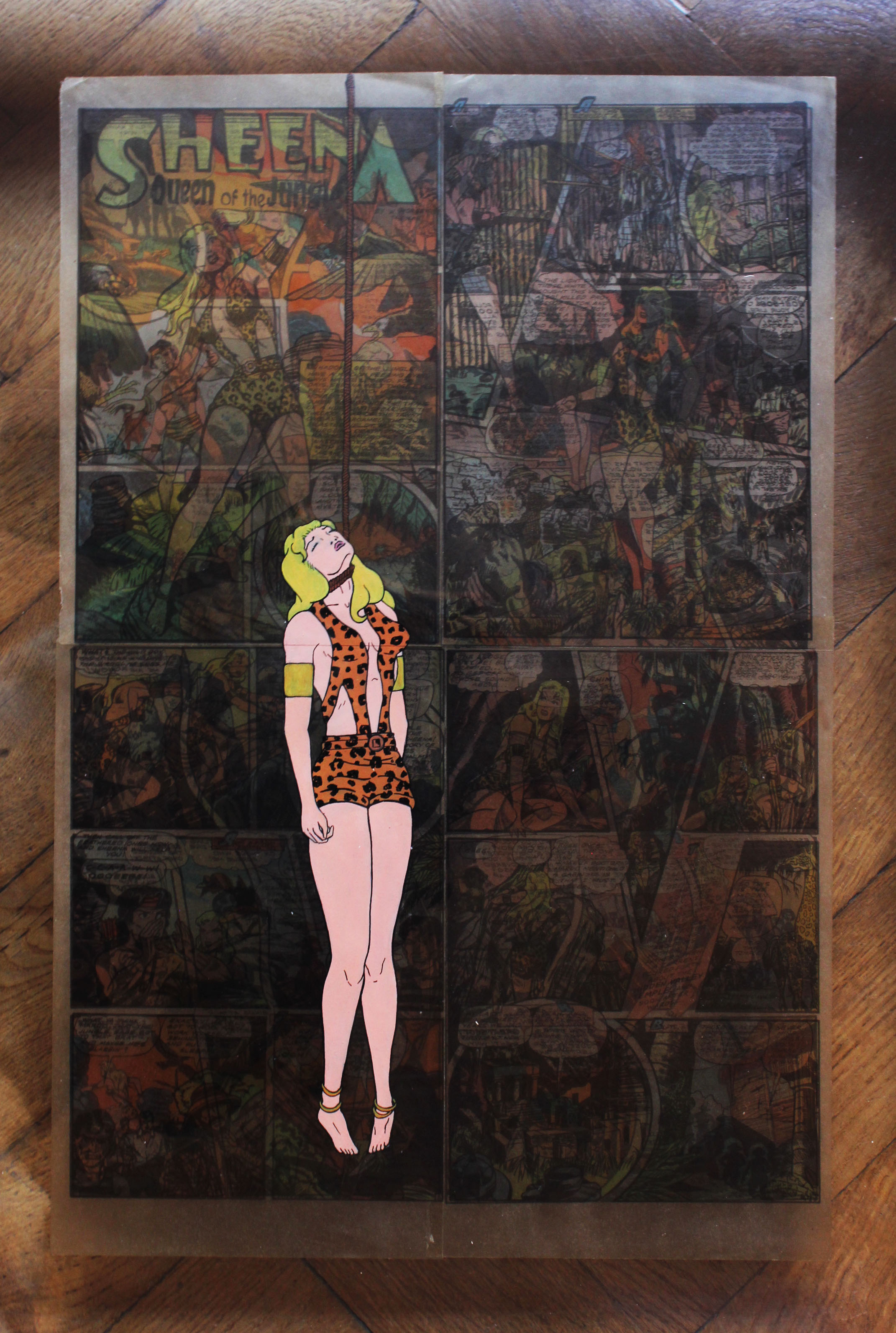

Matt Baker is considered by many to be the best of the good girl artists. His heroines were delicate yet powerful. The Baker Style, as it came to be known, can be recognized in each character’s slender legs and full hips topped by an impossibly curvaceous torso. More emblematic is the almost tangible energy with which Baker’s figures seem to dance and slide and shimmy from panel to panel and page to page. You can find his artwork behind the aging covers of Jungle Comics and Jumbo Comics featuring heroines like Sheena, Sky Girl (aka Sky Gal), Camilla, Tiger Girl, and Canteen Kate, to name a few. The bulk of his early titles come from a single publisher called Fiction House. Unlike the early Detective Comics (now DC Comics) and Atlas Comics (later to form Marvel Comics) who focused on what we now consider classic superhero characters, Fiction House made its mark by providing more titillating heroines for their audience.

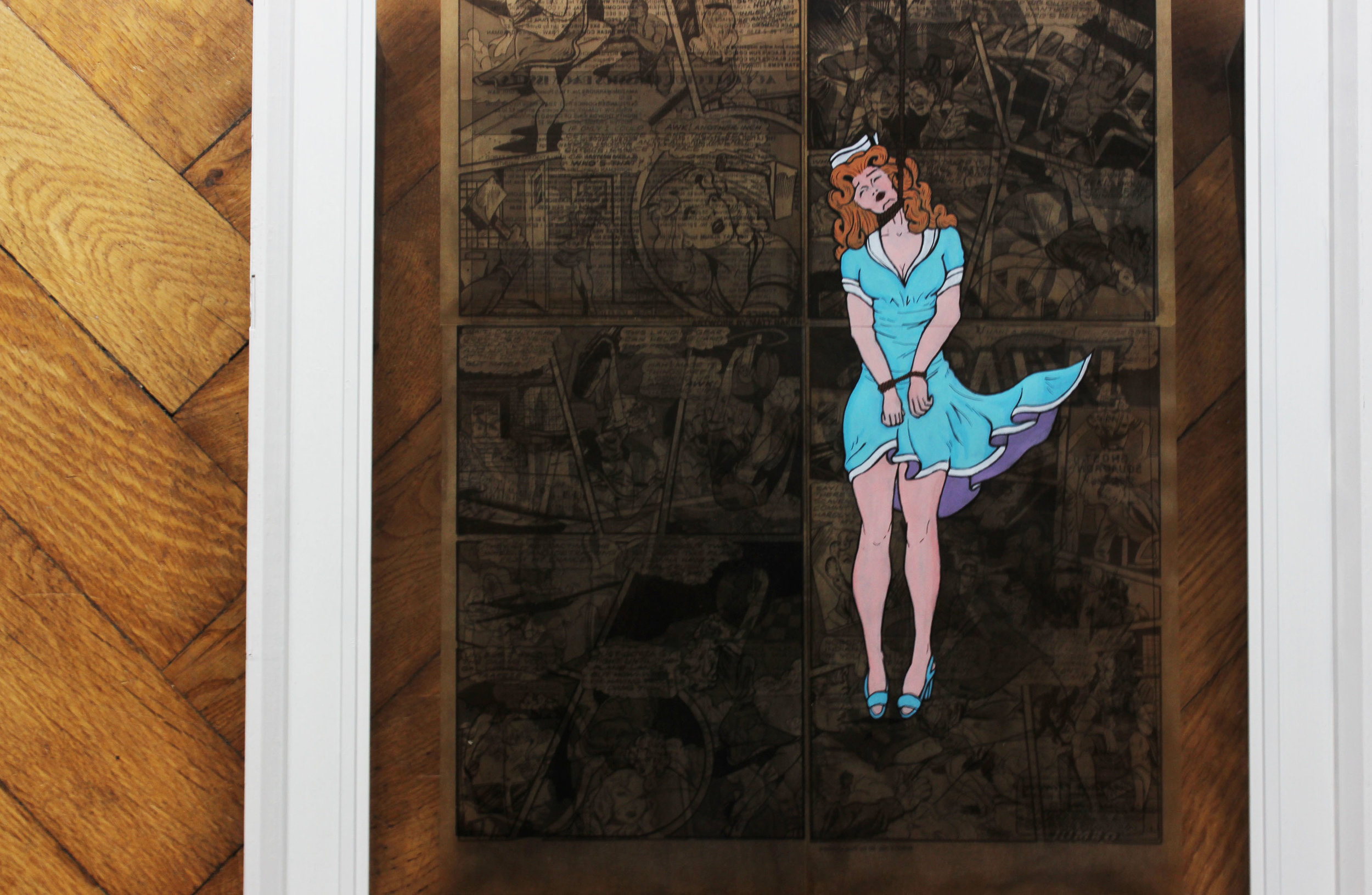

No publisher, however, played to male libidos more frequently or effectively than Fiction House. Women in short skirts, long slender legs, and exaggerated breasts adorned the covers of Fiction House’s comic books, while stories prepared for the publisher by the Iger shop beckoned randy young males with sexually suggestive and sadomasochistic images.

(Wright, Comic Book Nation)

The pulp pages of Fiction House books carried strong undertones of submission and sadomasochism, and occasionally overt references. Of course this is also true of work by other publishers. DC’s Wonder Woman and her creator William Moulton Marston have been scrutinized in recent years for the fetishized violence and scenes of bondage that can be viewed in many early issues. Fox Feature Syndicate published the well-known Phantom Lady comics, alongside other series. But Fiction House stands apart in its notoriety for developing scantily clad heroines alongside equally skimpy plot lines.

In his historical assessment of the effect of comic books on American youth, Comic Book Nation, Bradford W. Wright argues that commercial motive has been the driving force in the industry. Like most mainstream media, this steered its focus towards quantity over quality: mass appeal. Wright analyzes the literary formulas used by publishers to track changes in the audience preferences that direct the industry.

Audiences turn to formulaic stories for the escape and enjoyment that comes from experiencing the fulfillment of their expectations within a structured imaginary world… Formulas that appeal to audiences tend to proliferate and endure, while those that do not, do neither. As a means through which changing values and assumptions are packaged into mass commodities, formulas are the consequences of determining pressures exerted by producers and consumers, as well as by the historical conditions affecting them both.

(Wright, Comic Book Nation)

Literary formulas are narrative structures that denote a conventional way of treating a certain thing or person and are employed across a large number of individual works. These formulas capitalize on existing stereotypes to provide the audience with an accessible template for fictional characters or situations. Think of your favorite series. For the most popular productions, it's likely individual storylines matter less for your enjoyment of the experience than the repetition of a standard arch. More vivid examples can be found in the work of filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, who take stereotypical characters and situations beyond their conventional conclusions, enabling immediate immersion into the story with limited development. Recognition and fulfillment of audience expectations is central to continued consumption.

In the case of Fiction House, fantasies reinforced the contemporary gender and racial hierarchies. Heroines like Sky Girl and Sheena conformed to idealized stereotypes of white femininity. Purity and moral innocence were central to their storylines, often presented through stilted plots where the good girls fight organized crime or save dark indigenous populations from encroaching colonialists. At the same time, the good girls’ visual presentation stressed physical perfection. Large breasts and improbably long white legs were alluringly draped across several panels. Matt Baker and other artists went out of their way to draw female characters in suggestive positions to accentuate their physical features. By mixing sex with tales of moral--and often racial--heroism the good girls offered an appealing formula to the white boys and men who dominated their audience.

Fiction House was successful enough to warrant attention from early advocates of comic book censorship who feared the new medium was corrupting the minds of America’s youth. Along with a wide variety of comic books and pulp novels depicting violence, crime and fantasy environments, the publisher came under severe public scrutiny. Leading the censorship crusade was Dr. Fredric Wertham, the German-American psychiatrist who’s 1954 bestseller Seduction of the Innocent provided a comprehensive analysis of the dangers of comic books. Wertham’s chief concerns were that the positive portrayal of crime and violent images would desensitize children, while a barrage of direct and subtle sexualized references lured them towards sexual perversion. One of Baker’s covers for Phantom Lady was prominently featured in Wertham’s review to highlight these concerns. Though Wertham’s research methodology has since been discredited, in his time it was held in high enough regard to provoke the creation of a special Senate subcommittee on juvenile delinquency and spur comic book burnings around the country.

This attention meant little for Matt Baker or his legacy. He would never be known during his lifetime for his contribution to early comic book art. Aside from the subordinate role of comic artists, Baker’s publishers would have risked alienating a large portion of their audience if their artist’s race was revealed. And this wasn’t only true in Baker’s case. E. Simms Campbell was an African American cartoonist and illustrator who, also considered among the Firsts, was similarly praised for his ability to capture the female form. After a successful white illustrator suggested to a young Campbell that you could “always sell a pretty girl” in the industry, his work shifted towards depicting the fairer sex. Harem Girls, a series produced for Esquire magazine, is among his best known work and did indeed lead to steady commissions. Publishers of the magazines and periodicals that Simms illustrated intentionally kept his race a secret, worried in particular about their Southern readership.

The concerns from publishers about the reaction from their audiences were well placed. While publishers offered up their fictional stories, there were powerful and pervasive real life narratives at work about the threat of black manhood. Campbell’s and Baker’s artistic contributions directly confronted and complicated some narratives, particularly those created in the pretense of protecting of white womanhood.

The Black Rapist Myth

The Black Rapist Myth is built on the belief that black men are predisposed to desire white women and incapable of controlling their bodies when faced with this sexual desire. At its foundation are the pseudo-scientific theories of racial inferiority that were set during the colonial era and reinforced in America over centuries of slavery. The myth itself came together during the Reconstruction period as efforts to restore the economy also forced Southerners to raise up new social structures. Black people became economic and social rivals, leading to laws and social conventions aimed at limiting black ownership, promoting segregation and preventing miscegenation. Concerns over black wealth mixed with deep-seated fears of racial mixing and black reprisals for the injustices of slavery. Almost overnight, emasculated eunuch slaves became fearfully endowed black prowlers. Since that time, the Black Rapist Myth has stood as a safe haven for economic opportunists, white supremacists, and jilted lovers alike.

In publications around the country the myth was used to ignite a different type of passion in the hearts of white men. Narratives of criminality are often attached to groups perceived as cultural or economic threats. Early waves of Irish, Italian and German immigrants faced similar challenges in the United States. In contemporary global politics, Arab immigrants are frequently described as rapists, sexual deviants and thieves. In this case, it’s the persistent use of rape as a formulaic justification for extrajudicial, vigilante violence targeting black men that warrants further consideration. With no need for judge or jury, protection of white womanhood became reason enough for mobs to perform summary executions of alleged offenders. As one Memphis newspaper threatened in an article titled “More Rapes, More Lynchings”:

The crime of rape is always horrible, but the Southern man there is nothing which so fills the soul with horror, loathing and fury as the outraging of a white woman by a Negro. It is the race question in the ugliest, vilest, most dangerous aspect. The Negro as a political factor can be controlled. But neither laws nor lynchings can subdue his lusts. Sooner or later it will force a crisis. We do not know in what form it will come.

(Wells, Southern Horrors)

If the wish of the their audience was a validation of racial prejudice and a justification for active efforts taken to reinforce racial separation, a segment of the press seems to have happily obliged. Disproportionate newspaper coverage contributed to the staying power of the myth. Episodes describing the crimes of black men were presented frequently and in lurid detail. Playing on the expectations of their readers, reporters and editors tapped into nightmarish fantasies. Meanwhile, the white rapist was always an unfortunate exception to the normally “sexually civilized” white man. History would contend that any racialized form of rape was once the sole province of white males, granted by the ownership of black bodies.

At the height of the lynching crisis in 1892, journalist and activist Ida B. Wells made it her mission to debunk the Black Rapist Myth. Writing in Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, Wells catalogues the formulaic use of rape in newspaper articles to justify killing black men. Like the repetitive good girl plotlines, these newspapers all resort to variations on the same themes. In numerous cases, charges of rape, attempted rape or indecent conduct were used to hide consensual (but illegal) interracial relationships, remove economic rivals or to ensure vengeance for perceived social slights.

Lynching as Sexual Violence

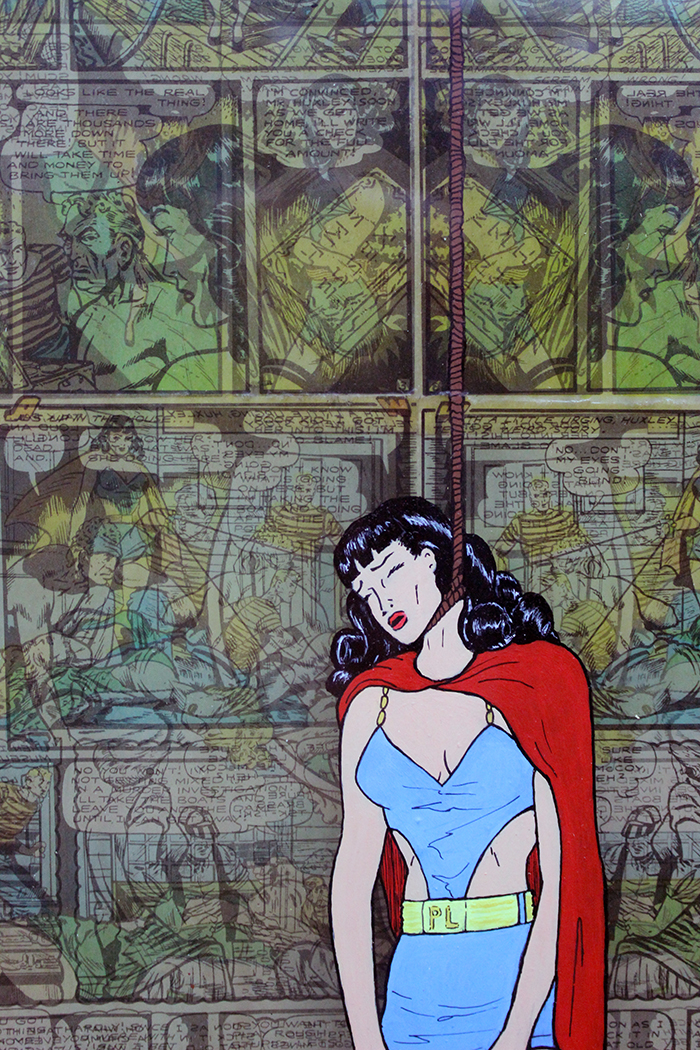

“Ho-ho! what a hangman I make! The police are blundering fools! But I am an artist!...My noose will fit around that pretty’s neck! ”

If the myth was the rhetorical tool used to stoke racial prejudice, lynching was the literal means of protecting white womanhood by destroying black manhood. Narratives of the purity of white women were forged in flames fueled by black bodies and hoisted high on the same ropes from which they dangled. Today we associate lynching almost exclusively with racially motivated violence, typically involving mutilation or burning of the body and hanging with a noose. The term gains its name from a Virginian farmer who took it into his own hands to maintain order in his town during the Revolutionary War. Lynch’s Law initially referred to mostly non-lethal, public punishment of white immigrants and law breakers. Community-oriented vigilantism was organized to fill gaps in official law enforcement. In step with the formation of the Myth itself, lynching became both increasingly deadly and increasingly racialized during the Reconstruction. By the late 19th century the term referred almost directly to acts of domestic terrorism against black people and supporters of racial equality.

Though Baker and Campbell both lived and worked in New York City, they were in no way removed from the effects of the Myth. Lynching was never as common in the North, but its history stretches across the United States, as do the effects of blanket narratives of criminality and hypersexuality on the minds and bodies of black men. In fact it was at the height of Baker’s career in 1955 that Emmett Till was violently murdered to secure the womanhood of Carolyn Bryant, at whom he was accused of whistling suggestively. Images of the teenager’s mutilated and bloated body tucked into a small coffin were seen across the country after his mother insisted on an open casket funeral. What would have been the reaction had Baker, his work known, returned to his native North Carolina, or ventured south to Georgia or west to Arkansas?

Even today, a racialized conception of rape is cited as a central reason for vigilante violence aimed at black people. Think back to the high profile case in 2015 of Dylann Roof, the 21-year old white South Carolinian who killed nine people at a church bible study. Carrying an automatic pistol, Roof sat quietly in the back of the church, waiting for the service to end before unloading his weapon at the group of black worshippers. Survivors of the attack claim that before Roof attacked, he proclaimed: “I have to do it. You rape our women, and you’re taking over our country. And you have to go.”

In a comic book, typically full of blood, violence and nudity, the erotic hanging theme is exploited. The average reader, of a generation not brought up on comics, may not realize the connection between sex and hanging...

(Wertham, Seduction of the Innocent)

Like the Fiction House formulas, the myth of the black rapist was pointedly aimed at (and promoted by) white men. Both capitalize on the idealized purity of white womanhood. Both exploit a similar sort of sexualized violence and domination. The gratification of submission and bodily dominance--whether those bodies are presented as lithe, white and feminine or black and brutish--was defined as an essential white, masculine privilege. Women who participated in Southern lynch mobs were considered “masculine” and young men who balked at joining the “party” were jeered as being effeminate.

Lynching is often read as a racial crime in order to preserve the masculine identity of both the victims and offenders. Even in the black community lynched men are more likely to be remembered as martyrs for racial justice than as victims of sexual abuse. Rape and lynching both operate as tools for psychological and physical control and follow a long history of tools used to assert white supremacy. The act of lynching is sexualized not exclusively in terms of penetration--though those cases exist--but in the sense of submission and dominance. Even when the alleged crime was not of a sexual nature, mob justice took on a peculiarly sexual tone. Victims were not simply burned or hung, but often thoroughly abused. Men were stripped naked and molested; their bodies roughly handled. They were maimed and literally disassembled, skin flayed and appendages removed as souvenirs. Some were castrated and others forced to consume their own genitals.

There was a certain perverse sense of propriety that accompanied this ownership. Like the good girls who were clothed just enough to preserve some sense of modesty, in many public images of victims of lynching special attention is paid to covering the corpses’ genitals. Postcard pictures were circulated of charred and mutilated bodies hanging from the noose, with a blanket draped carefully around the waist. What threat could have possibly remained? The mythologized black rapist and sexualized nature of lynching are intricately tangled together with other historical yarns that have led to the general hyper-sexualization of black men and the societal preoccupation with our genitals. Fetishized “big black cocks” carry the same notes of grotesque awe that were once used to provoke fear. The praise of black physique is preceded by the demeaning praise of physical specimens on the auction block.

Black history in America is often told as a vividly physical one. One imagines masses of black bodies shackled in boats, standing on auction blocks, trudging across cotton fields, running through Southern swamps, hanging from poplar trees, migrating northward, whooping and writhing between church pews, battered by fire hoses, sitting at lunch counters, marching through city streets, crammed into urban centers, scrambling for fixes, rioting in streets, piling into voter booths, jostling in prison yards and riddled with police bullets. To adopt the word “bodies” indicates where our worth has been defined: not in our personhood, but in our physical presence.

Concluding thoughts

Powerlessness. Knotted rope. A defiant stare. Or perhaps that’s a coquettish gaze on Phantom Lady’s face? Matt Baker’s keen skill at anticipating and serving the fantasies of a predominantly white male audience should not be dismissed as simple irony. Still, to me, Baker’s experience is as heroic as it is banal. His artistic talent and historical contributions deserve to be noted and respected. In a sense though, Matt Baker is representative of any black man who quietly navigates the everyday torrent of institutions and social conventions that paint them as more likely inmates than presidents and emerge unbroken. Certainly Baker was not untouched. It may be that these racial tensions are the very reason we know so little about the man himself, who reportedly kept his white friends and co-workers at arms length to avoid any trouble. His counterpart, Campbell, at times passed as southern European or Arab rather than black. Baker’s story is complicated even further by unverified remarks that he was a gay man. Performing his masculinity, then, required not just a consciousness of the fear and ire his race and gender might provoke, but also ownership or denial of his sexuality.

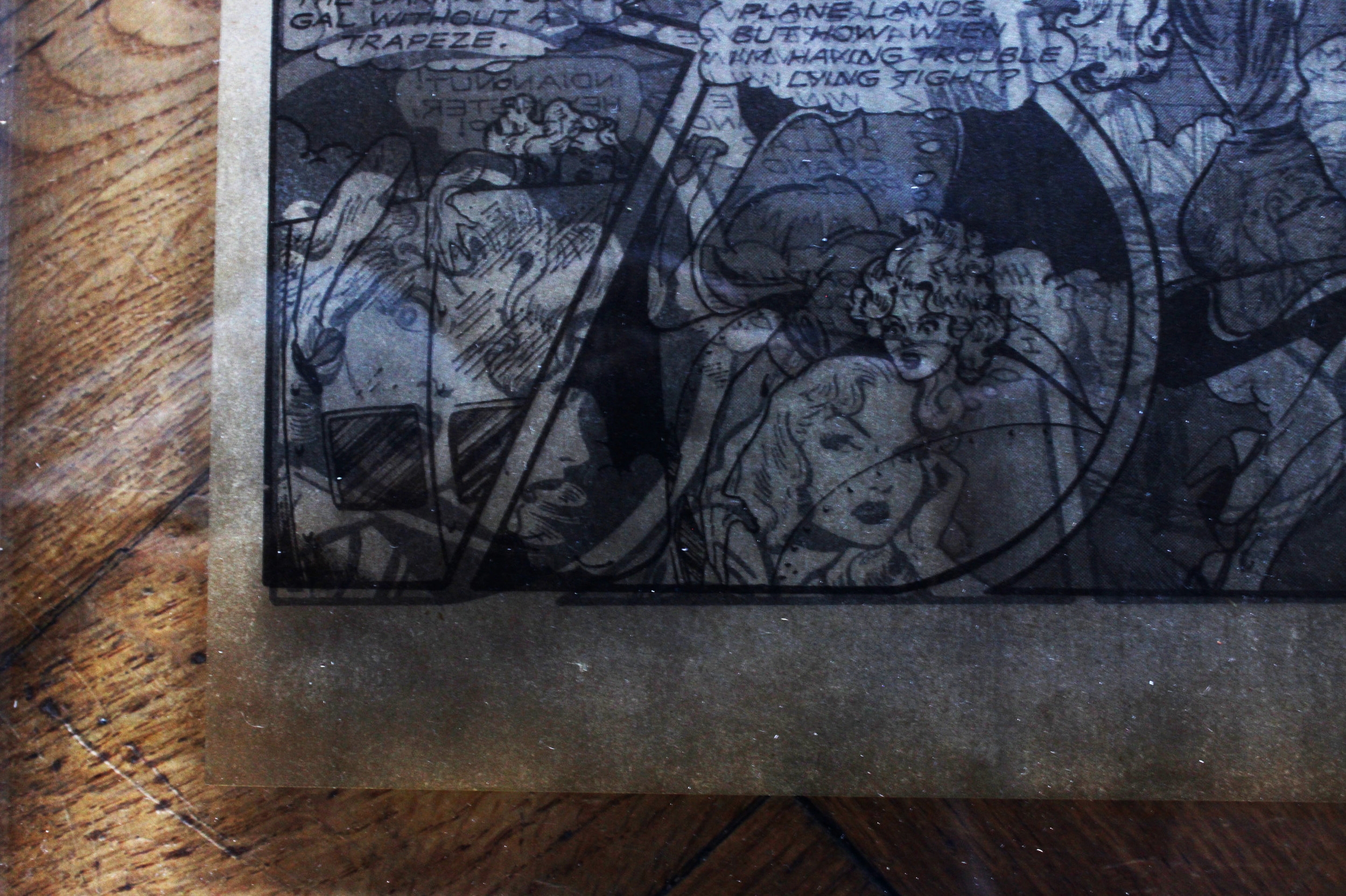

There are no easy answers here. The goal of my work is simply to reintroduce some of that tension that I find woefully unresolved in the praise of Baker’s achievements. For some initial pieces I’ve taken pages of Baker’s comic book panels as my canvas. Against the backdrop of Baker’s artwork, females figures are drawn to resemble the Baker style to retain their sensual currency, but introduce a small hint at the morbid balance behind the man’s work. Baker’s dainty cartoon pin-ups struck me as apt figures to replace real black bodies and perhaps illustrate the shockingly conflicted racial, sexual, political and gendered narratives at play. In this sense the good girls serve as surrogates. First they act as sexual surrogates replacing one sexual object for another without removing the author’s intent. Lurking behind these images the masculine urge for dominance is not diminished.

Lynching itself was mistaken as a heroic act to some communities. It was vigilante justice not unlike that championed in the pages of most comic books. America has a long and complicated relationship to vigilantism. Particularly in the frontier West and rural areas around the country groups like San Francisco’s Committee of Vigilance adopted the methods of criminals for the morally defensible purpose of community protection. Most often, though, these groups tended to target social outsiders as well as criminals. The subjective grey area in which vigilantes operate is often problematic outside of comic book narratives. Take for example the highly contentious case of George Zimmerman, who shot and killed Trayvon Martin and was later acquitted. Amid widespread fear of riots in some communities, many people commended Zimmerman for acting within his rights for self defense. Now, consider ex-convict Dwayne Stafford. After beating and seriously injuring Dylann Roof in a jailhouse shower, the black inmate received widespread praise, donations to his commissary account and pro-bono legal assistance that helped secure his release.

Not unlike the lynch mobs, neither of these men can be considered heroic, if only because their actions were motivated by fear or lust for revenge rather than any moral reason. For me the good girls heroines also function as surrogates to correct the misperception equating heroism and vigilantism. Posed in the same position as lynched victims, these beautiful vigilantes take their place.

Matt Baker died in 1959 at the age of 38 of heart complications that plagued him throughout his life. Baker’s life and work offer a unique microcosm in which we can watch one of the most gendered and long lasting segments of America’s racial conflict unfold. The lynching crisis has direct relevance to our current conversations about policing and the value of black lives. At the time, it was easy to be distracted by the circumstances surrounding the individual incidents of black men being killed and ignore the injustice of their deaths. The nature of their alleged crimes were abhorrent, especially to law-abiding members of the black community. And let’s be clear, not all of the allegations were false. There were black rapists and thieves who hung from some of those trees, just as there are criminals who lie dead today with bullets in their backs. The trend that remains is one of injustice. We’ve replaced our vigilante mobs with police officers and concerned citizens. What persists is that fear of the black criminal and the black rapist. The fear of some inherent threat in black manhood continues to provoke reactive violence which we call instinctive only because the narrative of its menace runs so deeply in our culture.

Sources

"Lynching Information." Tuskegee University Archives Repository. Tuskegee University. Web. 1 Nov. 2016. <link>

Wright, Bradford W. Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2001. Print.

Cawelti, John G. "The Study of Literary Formulas." Ed. Robin W. Winks. Detective Fiction: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1980. 121-43. Print.

Itzkoff, Dave. "Scholar Finds Flaws in Work by Archenemy of Comics." New York Times. New York Times, 19 Feb. 2013. Web. 1 Nov. 2016. <link>

"E. Campbell." King Features Syndicate: Famous Artists and Writers. 1949: n. pag. Lileks. Web. 1 Nov. 2016. <link>

Dooley, Michael. "Insider Histories: Black Cartoonist E. Simms Campbell." PRINT. Print Magazine, 3 Mar. 2015. Web. 1 Nov. 2016. <link>.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. New York: New York Age Print, 1892. Project Gutenberg. 8 Feb. 2005. Web. 1 Nov. 2016. <link>

Freedman, Estelle B. "'Crimes which startle and horrify': gender, age, and the racialization of sexual violence in White American newspapers, 1870-1900." Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 20, no. 3, 2011, p. 465+. 21 Nov. 2016.

Christopher C. Lovett, a Public Burning: Race, Sex, and the Lynching of Fred Alexander, Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 33 (Summer 2010): 94–115. <link>

Berstein, Lenny, Sari Horwitz, and Peter Holley. "Dylann Roof's Racist Manifesto: 'I Have No Choice'" The Washington Post. WP Company, 20 June 2015. Web. 1 Nov. 2016. <link>

Wertham, Fredric. Seduction of the Innocent. New York: Rinehart, 1954. <link>

Carter, N. M. (2012). Intimacy without consent: Lynching as sexual violence. Politics & Gender, 8(3), 414-421. <link>